The debate over the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on the art world has focused so far on how the impending technological revolution could benefit or disadvantage artists. But as AI becomes more of a feature of daily life, curators and connoisseurs are asking whether it can be a useful scholarly tool of benefit to art historians.

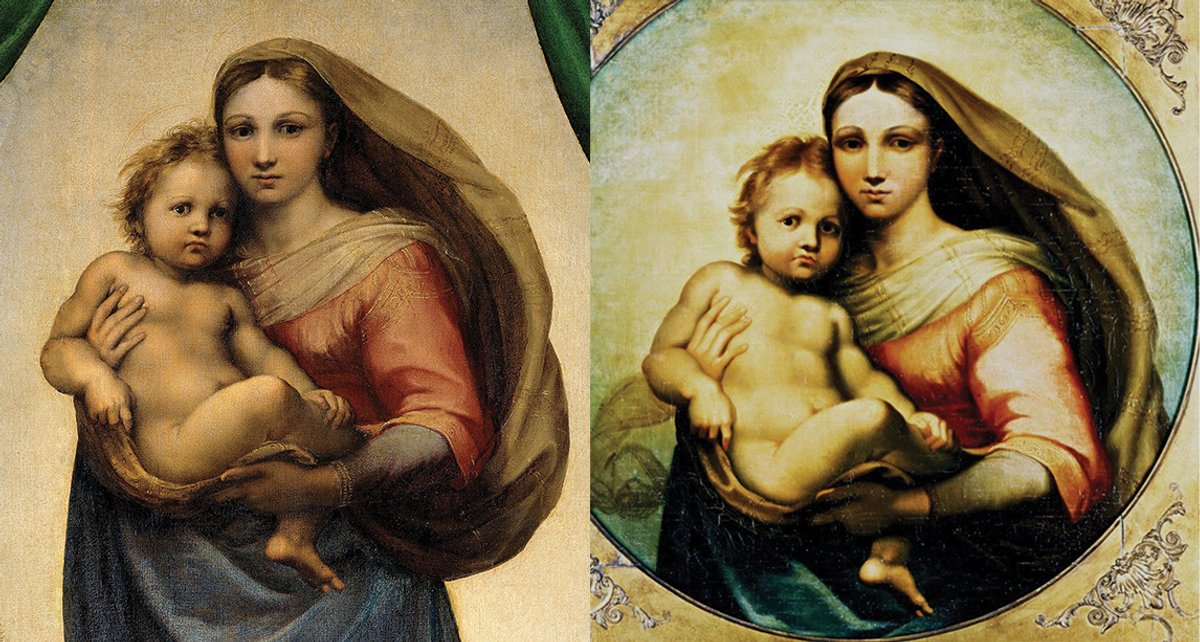

This question was raised during a recent furore over an attempt to attribute a new painting to Raphael, through the use of an artificial intelligence programme. Earlier this year, an analysis by two UK universities (Bradford and Nottingham) using AI-assisted, computer-based facial recognition concluded that the faces in the work known as The De Brécy Tondo—bought by the businessman George Lester Winward in 1981—were identical to those in a Raphael painting, the Sistine Madonna (around 1513).

The findings prompted a strong reaction from art historians including Angelamaria Aceto, a researcher in Italian drawings at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, who said that she would not support an assessment of authenticity that relies on AI. “True connoisseurship relates to the expert judgement of the trained eye,” she says, “and is so much more than mechanically matching brushstrokes and images.”

The case prompted questions about the validity and scope of the data sets used in such AI programmes. “The computer is only as good as what you put in, and I have seen no reporting on these computer authentications that asks the obvious question of what material the software is working from,” says another Raphael specialist who prefers to remain anonymous.

‘A false equivalency’

Hassan Ugail, the director of the centre of visual computing at the University of Bradford, who helped develop the Old Masters AI recognition model, tells The Art Newspaper: “It is essential to acknowledge that the expertise of art historians and scholars remains invaluable in understanding the historical and cultural context of artworks. However, incorporating AI into the process can provide additional insights and complementary information.” AI can bring a “further degree of transparency” into the process, he says, contributing to a clearer and more accountable approach to authentication.

For conservators, the issue is additionally fraught. Karen Thomas, the founder of Thomas Art Conservation in New York, says that in order to compare “like to like with any accuracy”, the AI would need to compare identically preserved paint layers across paintings. “If AI compares a perfectly preserved area in one painting to a restored area in another painting, or compares two paintings restored by different hands, we are inherently dealing with a false equivalency,” she says.

The value of connoisseurship is crucial to the understanding of paintings, Thomas adds, stressing: “I don’t see this as being replicated by AI.” She raises a number of questions: in the case of a poorly restored painting, will AI be able to see past the restoration to sense that something truer to the artist lies beneath? Or, conversely, can AI take into account a filthy varnish, wear or damage, and visualise how a careful restoration will bring the painting closer to how it should look if it were in good condition? She adds nonetheless that AI should not be considered useless. “I think it could be one tool of many used to try to determine authorship of a painting.”

The Swiss company Art Recognition, which was founded five years ago, is making its mark with an AI system which, it says, “evaluates the authenticity of an artwork swiftly and objectively”. The firm’s chief executive officer, Carina Popovici, says that “we meticulously assemble our data sets of images and cross-check them from reputable sources such as catalogues raisonnés. Our team of AI developers collaborates closely with an art historian who oversees and curates these images, ensuring their accuracy.”

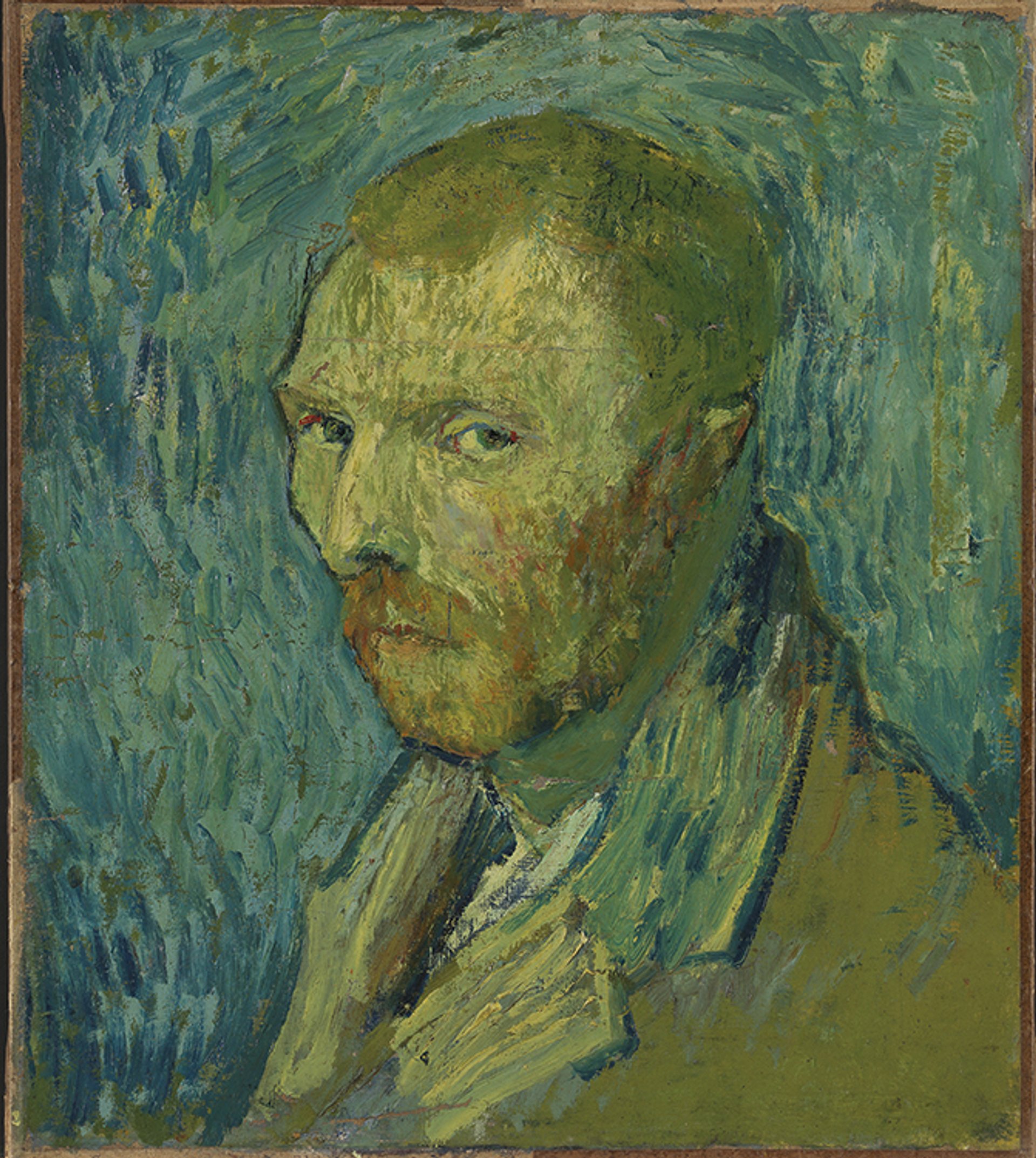

A long disputed 1889 self-portrait of Vincent van Gogh was assessed as authentic with a 97% probability using an AI tool, weeks before the Van Gogh Museum authenticated it The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Norway

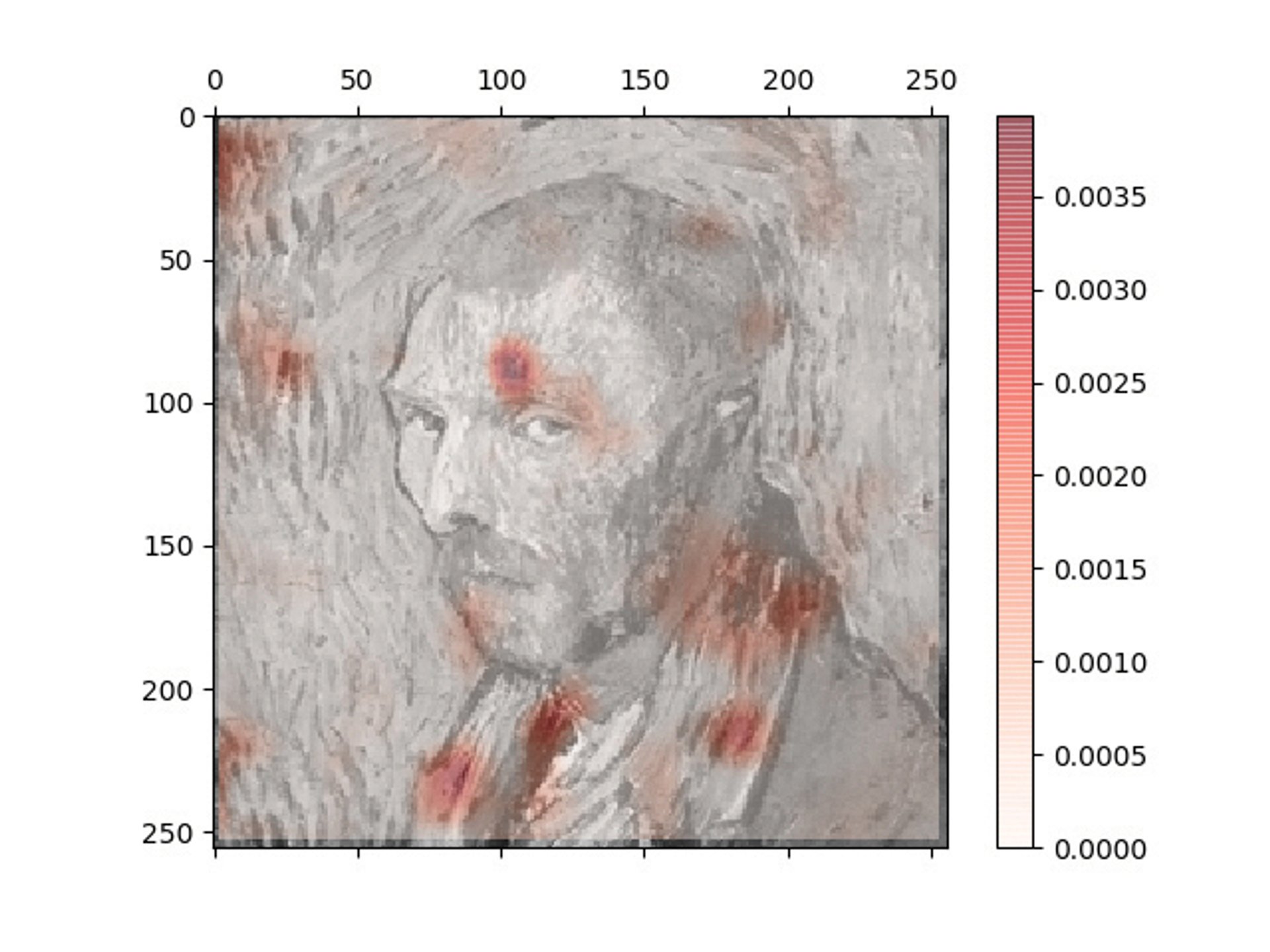

A heat map of the Van Gogh made by Art Recognition, used for the AI authentication. The crucial areas for the tool’s decision are marked in red. Art Recognition AG

The company’s detailed AI process—which includes “training the algorithm” so that the AI captures features pertaining to the analysed artist—has been used to verify contested works such as an 1889 self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh at the National Museum in Norway. “Our AI classified the Oslo self-portrait as authentic with a probability of 97%,” says the company website, giving a statistical appraisal. This verification came just weeks before a team of experts at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam ruled in favour of the painting’s authenticity.

Collaboration rather than rivalry

So, could Popovici’s AI service eventually replace art specialists? “We hold the view that our technology can complement the efforts of art experts. Our perspective is one of collaboration rather than rivalry,” Popovici says. She highlights that instances arise where art experts are unable to reach a consensus regarding the authenticity of specific works. Crucially, “in such scenarios, our method can help to effectively resolve these disputes”, she adds.

Both Popovici and Ugail point to academic peer-reviewed publications to back up their claims; Art Recognition collaborated with Eric Postma from Tilburg University in the Netherlands on an academic paper—“Art authentication with vision transformers”—which, Popovici says, is a “milestone for the acceptance of AI art authentication within both the scientific community and the art market”. Meanwhile, Ugail highlights a paper called “Deep Facial Features for Analysing Artistic Depictions”, presented last year at a conference in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

In an intriguing twist, Art Recognition has also analysed the de Brécy Tondo and has concluded that the painting is not by Raphael with an 85% probability rating according to the Observer. "We conducted our independent research on the image of the painting, which is available online. It's difficult to pinpoint why the results differ so much without reviewing the specifics. However, based on what I've read, the team at Bradford employs a face recognition algorithm, whereas our AI considers many other elements beyond just faces," Popovici tells The Art Newspaper.

Whether AI will eventually supplement the human eye remains to be seen and continues to polarise. Howard Lewis, the director of the Schorr collection of Old Master paintings, says: “I would not be prepared to accept an attribution based upon AI on its own as the gospel truth but it would also be churlish to altogether dismiss it. There is no doubt that AI, rather like blockchain, is here to stay but it remains a technological tool to enhance the human experience, not supersede it.” But the established London-based Old Masters dealer Johnny van Haeften is adamant. “I would not under any circumstances,” he says, “accept an attribution reached by AI.”